I arrived at Penn Station in NYC at 5:05pm. I had somewhere I needed to be at 5:45, in theory just a 10 minute subway ride away. As a wheelchair user, I knew that leaving only 40 minutes to get to my destination using a notoriously inaccessible public transit system was a risky move, but I was working with the time I had.

Silly me, hoping that a system designed to exclude disabled people would actually come through.

The Long Island Railroad train I was on pulled in on track 20, where the elevator to the platform hasn’t been in working order for months. There’s a lift available for anyone who can’t climb stairs, but you need a key to use it, and it has to be operated by an MTA employee. Of course, an employee was nowhere to be found when my train arrived. The clock was ticking. I scrambled around the platform searching for help, pushing the attendant call button, finally seeking assistance from a janitor who agreed to find someone. Several minutes later, I was finally on the lift—an agonizingly slow ride with a blaring chime. This little setback was the worst of it, I hoped.

I rushed to the subway and caught the C train to 59th Street-Columbus Circle. I was still making good time. When the doors opened at my stop, I was facing the biggest gap between the train and the platform I’ve ever encountered on the subway. I knew there was no way I’d get over the gap safely on my own. My front wheels would get stuck and I’d go flying.

I frantically called out for help, hoping I could figure it out and get off the train. Two conductors came out and told me they couldn’t help. By that point, I was holding up the train. Everyone was staring at me. I was trapped, told I had no choice but to ride the subway to the next accessible stop, change platforms, and double back.

So, where was the next accessible stop on the line? 125th Street. There were 9 stops and 66 blocks between accessible stations.

I internalized quite early in life that the burden is supposed to be on me to stay calm and deal with whatever access barriers come my way. But this time, as the train doors closed at 59th, something in me snapped. I began crying uncontrollably.

In the grand scheme of things, this was hardly the worst access issue I’ve encountered (and it’s far from the worst thing happening to disabled people right now more broadly, especially as COVID continues). And it was the umpteenth broken elevator scenario I’ve found myself in. Ultimately, it turned out to be an infuriating, demoralizing hour and a half of my life that ended okay. I made it to my destination, albeit 45 minutes late.

It wasn’t these particular 90 minutes that I wept for, though. A heavy sense of defeat washed over me as I wondered how much time I’ve lost to inaccessibility. To the endless calls I’ve made asking if I can enter a business or use their restroom. To the attempted moments of joyful spontaneity, only to be turned away by stairs. To the roundabout journeys to back alley dumpsters that leave me feeling like human garbage, because that’s the only accessible way to enter a building. To the seemingly endless waiting for access to the world around me, as though it’s a privilege and not a basic right for all.

I cried because I felt like a fraud. Just that morning, I’d given a presentation that included discussion of systemic ableism—barriers and discrimination built into the world around us. I’d been so sure of myself as I went through my talking points, highlighting the effects of ableism and inaccessibility, explaining how and why society must change. But as I sat helplessly on the train, everything I’d said rang hollow in my head. My gut instinct was to keep apologizing to my boyfriend, who was waiting for my arrival. No matter how many times he patiently reassured me this was out of my hands and that I was in no way to blame, my guilt was unshakable. I couldn’t reconcile how I’d gone from empowered activist to apologizing as if inaccessibility is my fault in the span of a few hours.

In my presentations, I generally use public transportation as an example of systemic ableism. Healthcare, education, employment, government…you name a system, and I’ll show you ableism at its core. But inaccessible transportation systems are particularly problematic, because so much of our existence and participation in other systems relies on our ability to get from point A to point B.

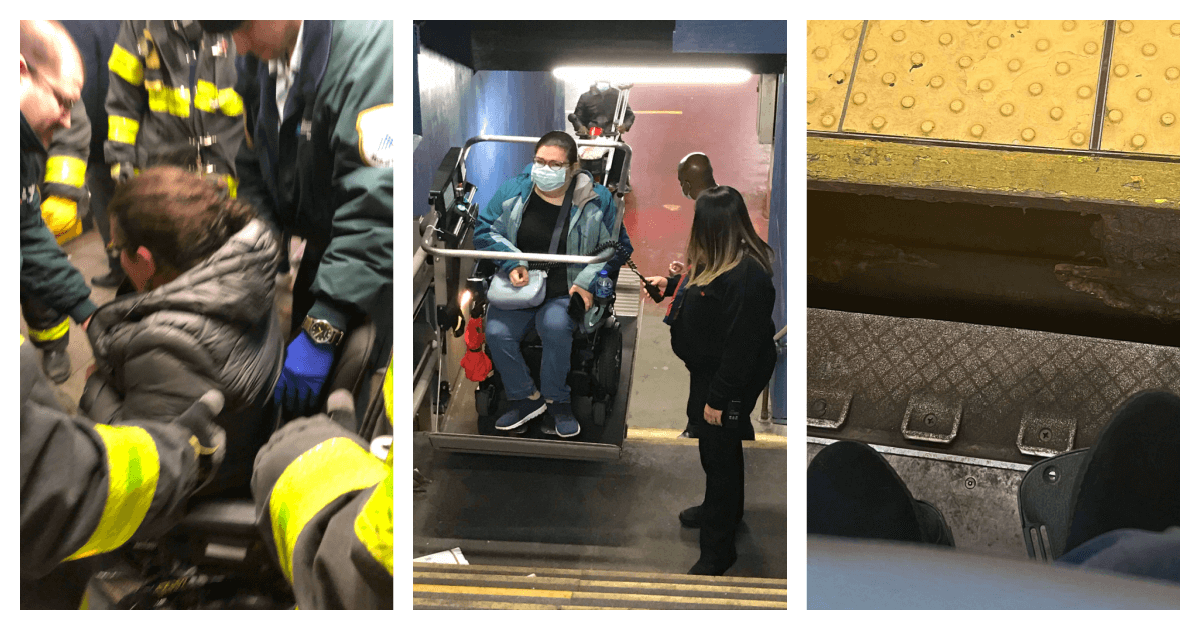

Disability advocates have been screaming into megaphones about transportation access issues for decades, and despite their best efforts, progress has been excruciatingly slow. Last year, I provided a declaration for class certification in a case against MTA. Earlier this year, the New York Supreme Court certified “a class of all people with disabilities for whom the use of stairs is difficult or impossible and who are therefore unable to access over 75% of the New York City subway.” I’m still hopeful change is coming, but remain haunted by nightmares of the time in 2018 when the fire department came to carry me up the stairs at the 14th Street-Union Square station because the elevator was out of service.

Rather than actually making a sustained effort to fix things, it seems like MTA bleeds money and accomplishes little. They pour funds into fighting lawsuits brought against them for inaccessibility and make redesign plans that will supposedly inch them closer to compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (which passed over 30 years ago). It’s inexcusable. But it’s reality.

I’ve had a lifetime of practice navigating inaccessible systems and advocating to change them. Yet I continue to wait for access. Disabled people around the world continue to wait for access.

How much more time must we lose to waiting?